Anna Kotomina

EXHIBITION “CINEMA OF REPEAT FILM” at Circular Kinopanorama

Evgeny Yufit, Alexandra Paperno, Natalia Vitsina, Dmitry Gutov, Taisia Korotkova and Svetlana Shuvayeva are presenting their works at the Circular Kinopanorama. When the cinema was built in 1959, contemporary art was represented by Tahir Salakhov, Yuri Pimenov, and Vera Mukhina.

Kinopanorama used a special, circular film camera with 11 lenses taking in all cardinal points to film views of the Black Sea Coast, Moscow, Leningrad and Tbilisi, the volcanoes on the Kurile Islands and the Carpathian Mountains.

Screenings provided cinemagoers with an opportunity to take imaginary trips across their country, as if they had walked into animated tourist postcards brought home from journeys along the Baikal-Amur Mainline, through Hero Cities, Soviet republics, and around an idealised version of the Soviet Union. The circular cinema, where all the walls constitute a screen, was designed in such a way that the audience could not see the edge of the movie screen and felt as if they had actually fallen into the film. During screenings at the cinema, a narrator speaking in a voice reminiscent of a radio announcer would pronounce phrases that had virtually lost all meaning owing to their regular use in Pravda and Izvestia.

Since then, time has stopped for the Circular Kinopanorama. In the tumult of the 1990s, the camera used to film panoramic cinema journeys was broken up and sold on the black market. Circular films are no longer made. However, by some miracle the unique projection system survived, together with six old films from the repertoire of the 1960s-1980s. The circular cinema is open again for business, forgotten by everyone on the margins of the noisy All-Russian exhibition VDNH, showing in rotation the six surviving films. It has been transformed into the cinema of endlessly repeating films, a permanent loop of itself. In the post-war years, the Cinema of Repeat Films was a commercial ploy that enabled the cinema to charge higher prices to screen films that no longer played elsewhere, but were still treasured by audiences. The Circular Kinopanorama with its never-ending repeat films operates at a loss, as a wormhole in time surviving in disregard of the gravitational pull of consumer society, where time means money.

As in the past, the audience stands still during screenings of the 20-minute films, as a flow of images circles around them, coming together in a colourful and senseless itinerary of impressions. As the circular camera was too heavy for the operator to hold, it was affixed to the roof of a car or train, placed on the deck of a boat, or hooked up to a helicopter. Modern audiences see the streets of Soviet cities with kiosks and passers-by attired in the fashions of the 1960s-1980s, slogans instead of advertisements, construction debris, cement fences, churches used as museums, desert tracks, smiling pioneers, and monuments to the heroes of revolutionary battles; everything that any individual would have seen when travelling by car, train or helicopter across the vast expanses of the Soviet Union. Our memory of the Soviet past is also based on the flow of numerous random images of sensations and fragments sweeping past us to eternity and timelessness. During the Soviet era, the narrator’s voice at the circular cinema resembled the voice of a bus tour guide, authoritatively telling the audience what to pay attention to, and what to rapidly select from the flow of spatial impressions. Today’s audiences are deaf to Soviet ideological recitations. They sink and drown in the flows of the circular projection, catching only the general dizziness akin to the sensation of time travel. The artists who participated in the “Cinema of Repeat Films” are the ideal spectators of the endlessly repeating film of the Circular Kinopanorama. At the exhibition they will show what they now perceive as most important from the stream of memories of the past. Fragments, details and images of Soviet films have become the point of departure of their travels through time.

Evgeny Yufit conducts an external examination of the Soviet ideological structure – something that is only possible today – selecting from amongst the dead and dying everything that can feed the “prevailing fatal idiom” of necrorealism. In his photographs, the dead look more alive than the living – one even doubts that the latter are actually alive. This sensation is reinforced by the effect of the still frame hewed from a film movement imitating life. The artist forces the viewer to vacillate when contemplating how to determine the border in his works between our world and the after world. The viewers’ doubts are akin to the agonies of readers of gothic fantasy, in keeping with the works of H. P. Lovecraft. They found it hard deciding on what to believe – whether the hero had gone mad or the castle was in actual fact swarming with ghosts.

In the stream of memories, Alexandra Paperno saw the “callous magnificence of domestic decor,” as in the case of colour photographs printed in three colours on a magazine insert for housewives from the time of plenty after the war. Alexandra perceives interiors as the same deserts as the camera of Alfred Hitchcock, freezing time in endless, anxious expectation – “suspense”. A dramatically-minded and sophisticated viewer of independent films would consider the appearance of a dead body in these interiors as logical, while dolls would suffice for optimistic members of consumer society. Take, for example, the mannequin doll used in forensic experiments in the performances of necrorealists on commuter trains and on the streets in the mid-1980s.

When portraying the interiors in her three-picture frame series, Alexandra shifts the perspective, creating the vertigo effect. In the films of the mid-1950s Hitchcock diverged from Hollywood’s gold standard, stipulating that the perspective of the camera be combined with that of the director and the audience, and instead conveyed through the camera the viewpoint of the actor who is feeling dizzy. Hitchcock’s film “Vertigo“ came out in 1958, one year before the construction of the Circular Kinopanorama. Soviet experimental directors, who shot circular films, used Hitchcock’s approach to entertain the audience. By using a circular camera on a cart in the 1987 film Tale about Rus (1987), and suspending it from the hook of a pillar crane, hovering over new buildings in the film Hello, Capital! (1966), the directors Evgeny Legat and Igor Bessarabov forced the audience to sway out of a loss of balance and giddiness.

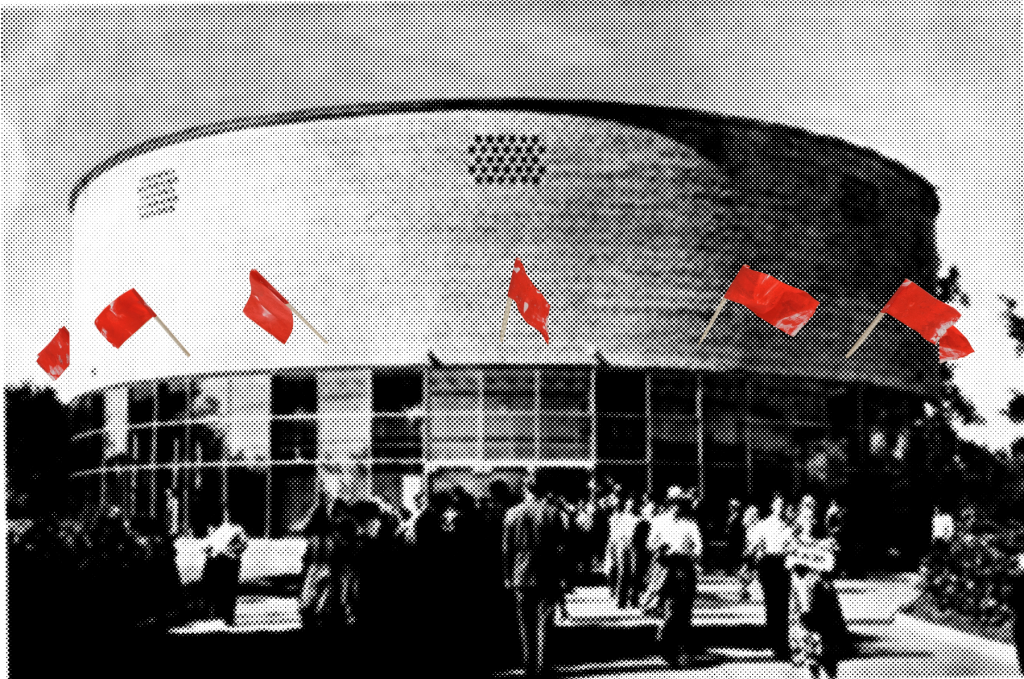

Alexandra’s second work at the exhibition is called Colouring. Eleven red flags have been installed on flagpoles located around the entire perimeter of the façade of the Circular Kinopanorama. A red flag appears on the mast of the battleship at the end of Eisenstein’s film Battleship Potemkin. To make the flag appear red on the ship’s mast in the black-and-white silent film, the editors had to colour in a large number of the film frames. The red flags on the façade of the Circular Kinopanorama have also been coloured manually in an expressive manner. The 11 repetitions of the flag’s colouring create the impression that the film frames are moving. The eleven flag frames accord the old cinema a similarity to the celebrated battleship in the film, no longer sailing through the lines of enemy ships as in Eisenstein’s film, but instead through time.

Natalya Vitsina examines through the flow of time two works that were created in the same year: Vera Mukhina’s sculpture Worker and Kolkhoz Woman and Grigory Alexandrov’s film Circus (1936) based on the screenplay by Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov. Both works of art were standards of Socialist Realism. The artists helped create and cultivate in people the ideal model, the prototype of Soviet man. This model was subsequently replicated countless times, as in the “Song about the Motherland” from the film Circus on a Soviet gramophone record displaying Mukhina’s sculpture. The record would have been lost in the turmoil of modernity, were it not for the artist’s attentive eye.

The ideal model of man, a part of Soviet utopia, could only exist in the isolated, artificial, ideological space, which is reminiscent of the cylinder of a circus, where the audience can either focus on the artists on stage, or look at other members of the audience in the opposite stands. The closed circular hall of the Kinopanorama created and maintained the image of the ideal Soviet Union, while the closed world around the circus arena in Alexandrov’s film facilitated the establishment of the image of ideal Soviet people.

The model of Soviet man was born in a closed dialogue with American mass culture. The main protagonist of Alexandrov’s film was the aerial gymnast Ivan Martynov, who appears in the circus act “flight into the stratosphere“ as a superman, anticipating by two years the release of the famous American cartoon strip about superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster.

In her paintings and graphic works, Natalya Vitsina studies the prototype model of Soviet man, conceptualises it, and disassembles into fragments as in the case of reconstruction (or deconstruction), an experience repeatedly suffered by Mukhina’s sculpture. Vitsina mixes the fragmented reflections of the sculpture Worker and Kolkhoz Woman and those of Alexandrov’s film in the cylindrical, closed circus hall of the Circular Kinopanorama, returning to the model prototype of Soviet man, authenticity obliterated by time.

Taisia Korotkova focuses on the inconceivable nature for common man of the goals of experiments conducted to master the boundless expanses of space. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s plaster figure has been placed in one of two diptychs inside the warm, wooden interior of the terrace – workshop, which has been transformed into a memorial museum of the scientist. The second work is a black-and-white frame – panorama, where a rocket in an imagined 1946 takes off from a cosmodrome in the centre of Moscow near the completed Palace of the Soviets from a 1935 science fiction film about conquering outer space called Space Flight. Tsiolkovsky was a consultant on the film and expressed satisfaction with the results of the work. Based on the subject of the film, a professor is not allowed to go to the moon, and an endless stream of dogs and cats are sent instead as experiments. However, he decides to secretly violate the ban. Looking at the picture frames, one might assume that Professor Tsiolkovsky managed to deceive all his sceptical bosses and, placing a gypsum double in his workshop, flew on the rocket to the moon. However, it could also be assumed that the scene from the film, where the scientist was a consultant, has become part of the museum exhibition. In the museum space, it is already impossible to differentiate between the actual individual and the film hero, and the grandeur of implemented projects from the hyperbole of projects that were not implemented. Experiments that cannot be reduced to any practical use may continue endlessly. The works of the artist build a bridge across the precipice of a museum containing an infinite number of experiments.

All the films, including the circular panoramas, began and ended with titles. The first titles – the title of the film – captured the attention of the spectator and settled in his memory – and provided commentary about the film, a synopsis. Dmitri Gutov writes phrases in white paint on a black background. The graphic design in the spirit of the titles in the glory days of the Circular Kinopanorama, enables the audience observing Dmitri’s phrases to assimilate the ascetic composure of the aphoristic zen calligraphy. The white phrases on the black background require serious attention, as in the case of instructive chalk writings on the school blackboard. You want to believe that they will also summarise the plots of the fragments of endlessly engrossing films that have not been shot or have been lost, like the laconic, black-and-white captions of a silent film.

When the circular camera was carried out past fences, kiosks, and the blank walls of the suburbs inscribed with famous words, it was simply turned off to save film. Svetlana Shuvayeva collected these inscriptions, the excluded fragments of the everyday Soviet visual landscape, and transformed them into patterns on dresses. Svetlana Shuvayeva’s dresses are reminiscent simultaneously of the breakthrough to the “new daily life” and the geometric functionality of the clothing and fabrics used by Varvara Stepanova in the 1920s, and the “hidden destructive power, impudence, and aggression” of the wonderful and seemingly kind young heroines of the film Margaritas (1966) by the Czech “new wave” director Vera Khitilova. Soviet filmgoers at the end of the 1960s could differentiate between the looks of the well-dressed and joyful Czech girls among the flow of street life in the 1968 panoramic film Summer in Czechoslovakia. The film did not remain on the repertoire of the Circular Kinopanorama. The film stopped being shown after the Prague Spring. Svetlana Shuvayeva’s artistic sensitivity focuses on the fleeting images erased first and foremost by the censor. Returning them to modern viewers, Svetlana, just like the other members of the exhibition, performs her own revision of the collective memory of the Soviet past, stopping the headlong passage of time for the visitors to the exhibition, and marking down possible individual tours within this stream.

The extremely personal contribution of the artist may do more to preserve the memories of the past than the archiving efforts of a museum employee. The exhibition “Cinema of Repeat Films” at the Circular Kinopanorama is in tune with the museification project of this unique memorial to the history of the Thaw that the Moscow City Department of Culture has been preparing for several years. The Circular Kinopanorama invites visitors of the exhibition to take a trip in time with Evgeny Yufit, Alexandra Paperno, Natalya Vitsina and Svetlana Shuvaeva, Dmitri Gutov and Taisia Korotkova.

Anna Kotomina, Artistic Director of the Circular Kinopanorama, The Moscow Cinema State Institution of the Moscow City Department of Culture